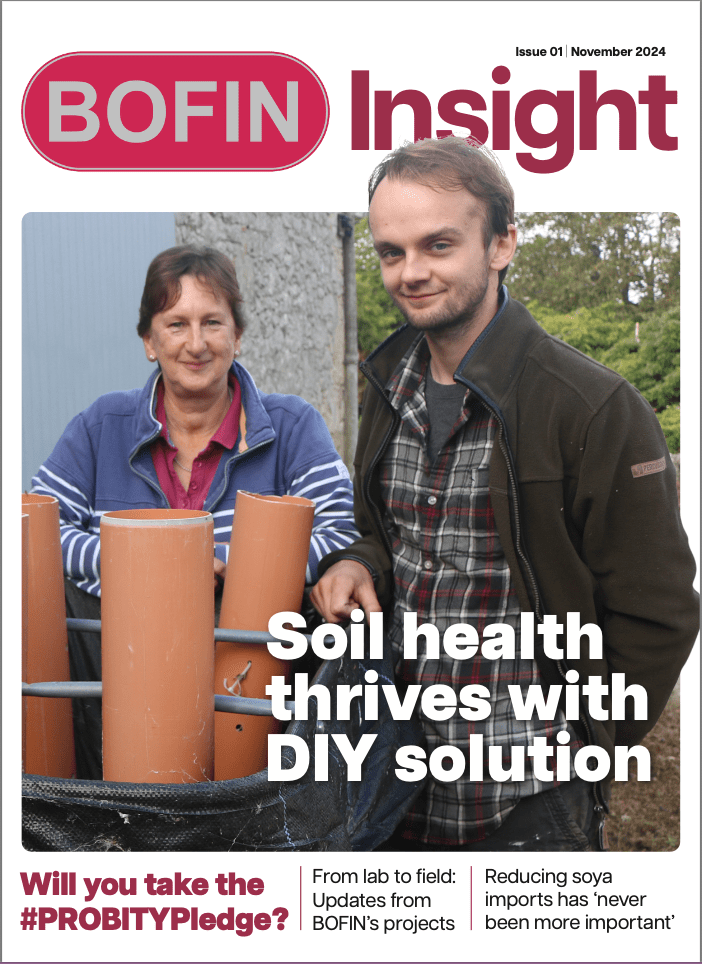

On the Isle of Wight, Rachel and Jacob Holmes are keen that science steers the course on their journey into regenerative agriculture.

At the side of the yard are three IBC containers. The plastic tanks have been removed, and in their place is a black semi-permeable membrane, with each container about half full of what looks like compost. But it’s the four-inch diameter terracotta-coloured drainage pipes protruding from the IBCs that denote their purpose.

“The key requirement of a Johnson-Su bioreactor is that the compost must be kept aerobic,” explains Rachel Holmes.

Cable ties keep the pipes no more than 30cm apart, while holes drilled down their length keep the bacteria, fungi and other microbes multiplying in the compost.

The aim for the microbes in the bioreactor is to breathe new life into the loam over brash soils of the 340ha arable farm Rachel farms with her son Jacob on the Isle of Wight. The farm business, Independent Farms, has set a course on regenerative agriculture, reducing cultivations and introducing cover crops into a rotation that includes wheat, wholecrop rye and oilseed rape with additional breaks of stewardship legume fallows.

“The soils have been very intensely farmed over the years,” says Rachel. “The turning point was the drought of 2022 – cover crops simply didn’t germinate, and you just wonder whether there’s enough life in the soil to pull it through periods of more extreme weather.”

She takes a trowel and, leaning over the side of an IBC, doesn’t have to dig too far to find several worms, helping the process of breaking down the raw materials into a rich soil-like matter with an abundance of microbes. “There’s no question there’s life in this compost – Jacob has confirmed that by taking regular samples and studying them under a microscope,” continues Rachel.

“The big unknowns are whether we are being successful with transferring them into the field, and the difference they’re making to the health of the soil and the crop roots within it.”

This is why Rachel has joined as a Root Ranger with the TRUTH project. Independent Farms is one of 20 farms across the UK conducting crop trials and taking intensive soil samples to understand the microbial community within it, and the effect of applications of products or mixes claimed to be beneficial.

For Rachel and Jacob it’s the compost ‘tea’ they produce that’s under scrutiny. This starts its life in the Johnson-Su bioreactor – a DIY kit developed by Dr David Johnson, a molecular biologist at the University of New Mexico, and his wife, Hui-Chun Su. The compost created in this set-up is then brewed to produce an extract which is sprayed on the land or can be applied to seed.

Rachel explains that the key to the process is finding the right mix of raw materials for the bioreactor. “We’re keen to use material found locally and have also added spent coffee granules from a local café. It’s quite addictive – once you get started you get hooked on finding the right recipe.”

A tag on the side of this IBC reveals woodchip, manure and coffee are the ingredients being turned over by the worms. In the next-door container hay has been added, while a mix of hay, fresh-cut grass, manure and chopped rye complete the trio.

The mix can spend over a year going through its process before it’s ready, and while it doesn’t need to be turned, like regular compost, it should be monitored and kept moist. Just to the side, in the yard, there are two containers of vermicast. “It’s essentially worm poo,” explains Rachel.

“You can buy it, but ours is home-grown from kitchen scraps. A bag each of the vermicast and compost are dropped into the brewing container, like two giant tea bags.”

Wandering over to the spray shed, another set of IBCs, this time with plastic tank intact, form the brewing set-up, and Jacob talks through the process. “The bags are a 400-micron mesh, that can let microbes as large as nematodes through, but not the residue. Each 1000-litre tank is filled with water and we add one litre of Actiferm, a liquid mix of fungi, yeast, lactic acid bacteria, phototropic bacteria and actinobacteria, along with a dollop of molasses.

“Air is then bubbled through the tank for 24 hours and it’s ready to apply. That’s the tricky bit – you have to be sure you can spray at the right time or the mixture will go past its best. Extract with twice as much bacteria as fungi is the ideal, and according to the literature, an application of around 200l/ha puts down 60 million bacteria and fungi per square metre.”

Jacob has a voracious appetite for information on all aspects of soil biology he’s gleaned from the likes of Dr Elaine Ingham, the webinars he’s attended and contacts he’s made. “Living here on the Isle of Wight it can be difficult to get to events geared towards understanding soil biology. But we’ve been to Groundswell and the Green Farm Collective event – both of these have proven useful, especially to hear other farmers discuss what they’re doing,” he says.

He collates this all into a referenced document that helps him understand the microbes he monitors using his microscope. Much of the data has also been brought into a handy app he’s developed that aids the somewhat complex calculations he makes to ensure the right balance of microbes in the extract brewed and applied to the fields.

“Preparing and applying biology to the soil through a sprayer is totally different to using chemistry as it’s a living material that changes by the hour. For instance, bacteria multiply in the brewed extract every 20 minutes, fungi typically every 4-6 hours, protozoans multiply threefold in 24 hours, while that’s too short a timespan for nematodes to multiply. But maintaining the right balance is crucial, as they all have different tasks and respond differently to environmental factors in the field.”

And it’s this response in the field that has been the missing piece of the jigsaw. Jacob has gone to admirable lengths to explore the microbiome he can introduce to the soil, its interaction with the specific environmental factors it faces, and the issues with bringing it, in the right balance, to where it can get to work.

“This is a brand-new school of science we’re just beginning to learn,” he enthuses. “There are so many living organisms in the soil and in our attempts to harness them, we’re not sure whether we’re creating brown gold or doing a sh** job of being King Midas. The science is good, but without results it’s just witchcraft. Anything we can do to fill that void will help turn the witchcraft into wizardry.”

Found in:

Issue #1

Will you take the #PROBITYPledge?

Root Rangers to trial ‘remarkable’ wheat

Turning witchcraft into wizardry

Reducing soya imports has ‘never been so important’

Cracking the code for ‘slug-resistant’ wheat