UK agriculture, and the economy it underpins, are in a parlous state. The crumbs of comfort cast to farming pioneers hold promise for a new dawn for productivity growth if they can be backed up with long-term commitment, argues Tom Allen-Stevens.

As a farming innovator in the UK, you can make the case that prospects have never been better, especially for the farmers exploring new tech and developing new practices. Equally, you could argue that farming pioneers have never been so sorely betrayed. That, coupled with a dire picture of productivity, means UK agriculture may stand on the precipice of its greatest depression of the last 100 years.

So why the dichotomy?

On the plus side sits the Agri-tech Strategy. This £160m package launched in 2013 comprised the Agri-Tech Catalyst plus £90m of funding to get the four Agri-Tech Centres underway, three of which have since come together as UK Agritech Centre. Since then, there’s been the Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund putting up to £90m into precision, data-driven and novel production systems. Most recently it’s been Defra’s Farming Innovation Programme (FIP) and related competitions.

It’s difficult to know exactly how much funding has gone into these initiatives, as successive governments have been adroit at spinning previously announced funding as new cash. But there are two important aspects that should cheer you up: firstly, that there is any funding at all, and also that farmers are directly receiving it.

The funding amounts to about £50m per year. That’s 2% of Defra’s £2.5bn budget – not a great percentage to spend on R&D, of an amount which, despite current ministers’ assertions, is actually the smallest farming budget in real terms since the Second World War. But this cash does have a galvanising effect if spent well, leveraging in wider industry support in collaborative projects, so your £50m goes a long way.

What’s more, in 2020 the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy reported benefit-cost ratios from the UK’s Agri-Tech Catalyst of between 5:1 and 9:1 so agricultural R&D is recognised as a good spend of taxpayer cash.

And increasingly that cash is being spent on farmers. The strategy has been to build the infrastructure first (e.g. Agri-Tech Centres), then support industry, through funds such as large and small R&D partnerships and Farming Futures R&D. The aim of these later funds has been to involve farmers, and projects that have set out to do so have been more successful, both in winning funding and in their outcome.

Finally, the farmer-focussed Accelerating Development of Practices and Technologies (ADOPT), which arguably gets the lion’s share of current Defra R&D spend and is tipped to be the most secure going forward. BOFIN, along with other members of the Farmer-Led Innovation Network (FLIN) pushed for and helped shaped ADOPT with Defra and the result is a good scheme, although it has its teething problems, that we’re now working equally hard to sort out.

The fund supports true farmer-led innovation – if you have an idea, BOFIN can help you turn it into a £100k, two-year project. You then focus on getting solid evidence for the practice or tech you’re exploring while we manage milestones, reporting and liaison with Innovate UK, who settle the cost claims.

The original fund of £44m announced by the previous government was hastily reduced to £20m. Hundreds of farmers are involved, gaining proper funding for R&D work on their own farms. BOFIN also helped secure a rise in the default rate farmers are rewarded for their time, from a derisory £176 to over £250/day.

There are hundreds more now involved in FIP. This includes up to 100 farmers joining BOFIN’s projects this year, receiving cash payment for on-farm trials. Since BOFIN launched in 2020 we’ve paid out over £350,000 to our farmer trialists.

This begs the question, will this support continue?

Recognition for farming tech pioneers has been long promised and slow to arrive. But if we take cheer from this small success, we should equally view it with caution.

When Government looked to shape Environmental Land Management, it was these pioneers that joined the ELM Tests and Trials and co-developed many of the Sustainable Farming Incentive (SFI) options. It is down to them these nature-based solutions received extraordinarily strong uptake, building soil health and environmental resilience into agricultural systems. It’s a remarkable achievement of some uniquely skilled staff within Defra coupled with pioneering farmers’ ingenuity.

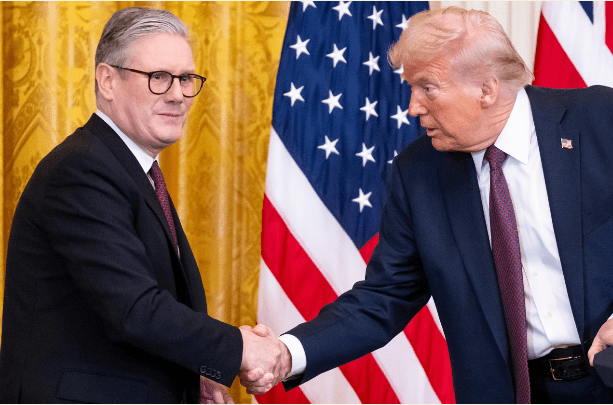

But the chaos we’ve witnessed since the new administration in 2024 is a shambles. Farmers cannot plan a resilient, productive crop rotation if one element within it flips in one day from delivering £350/ha return to zero on a minister’s whim. It is a betrayal of everything that was achieved by the pioneers of nature-based solutions. Thank goodness the incompetent ministers responsible for this mess have moved on – it’s up to the new ministers to work with us to repair the damage.

That’s if it’s not too late. Baroness Minette Batters has now delivered her much-anticipated review of farm productivity to Defra. It has 57 recommendations along with a dire warning that farming is in a parlous state: stats from Defra and Strutt & Parker show that 50% of farm businesses fall below the income level needed to match median household earnings.

OECD figures show the average annual agricultural output growth in the UK in 2013-22 was a sluggish 0.47%/yr. Total factor productivity (TFP) is less than half the global average rate and the latest stats from Defra show this is falling. This really matters to the UK economy – farming may make up just 0.6% of GDP, but while agricultural productivity flatlines, food prices will continue to rise.

Farming pioneers can kickstart a recovery. Countless studies have shown that farmers learn best from other farmers, but someone has to be first and there’s no first-mover advantage for these champions.

So current government ministers must not treat the pioneers of farming tech with the same disdain their predecessors showed for the pioneers of nature-based solutions. If they do, the hundreds embracing the new R&D structure and shaping future farming will turn their backs on this new era of discovery – leaving UK agriculture facing decline.

ADOPT is a hard-earned achievement for farming pioneers. It’s a symbol of farmers’ ingenuity and its potential to lift agricultural productivity. Defra ministers need to recognise and double down on their support and endorsement but the rest of industry also needs to embrace it. Farmers get a fraction of government R&D spend, but few commercial organisations pay farmers a penny for their contribution to honing new products and services.

BOFIN will continue to uphold how valuable farming pioneers are to the UK economy. Thanks to your support, we sit in the right places, talk to the right people and our views, which are your views, are respected as authoritative. All you have to do is continue to bring us your bright ideas, feed back and resonate your findings, and work with us to bring them to fruition.

Found in:

Issue #3

Celebrating 5 years of farmer-led innovation

From guesswork to ground truth: mapping the future of pest control

SLIMERS Project advances in the battle against slugs

‘Slug trials’ test nematode application techniques

Wholecrop beans are a win-win for livestock performance and sustainability

Gaining ground with novel wheat lines

Landrace wheats on trial

Rooted in Research

It’s easy to ADOPT, harder to commit