How researchers have harnessed tech to detect slugs

Researchers from the UK Agri-Tech Centre and Rothamsted Research have identified a high-tech method to detect the grey field slug or Deroceras reticulatum.

Their discovery paves the way for both automated in-field monitoring and the development of novel, precision slug control strategies, including the use of biocontrols and biorationals.

In a paper published this week, the researchers describe their studies which explored the potential of multispectral and fluorescence imaging to detect slugs. Results showed that multispectral imaging can be used to identify D. reticulatum and differentiate the pest from common agricultural field-surface materials.

They found that as few as five wavelengths were sufficient for slug detection including from the UV (365nanometer or nm), blue (405 and 450nm), green (570nm) and NIR (880nm). Fluorescence imaging failed todetect a slug-specific signal.

The paper brings together data from two Innovate UK funded projects – SlugBot and SLIMERS – which were supported through the SMART and Defra’s Farming Innovation Programmes, respectively.

Their work focused on the grey field slug, one of the most economically significant slug pests and a major cause of crop damage.

Historically, farmers have monitored slugs using traps or visual observations, however, these manual approaches are labour intensive and reduce the scope of monitoring. Automated slug detection could provide more detailed insights into slug populations and support the development of precision slug control strategies.

Technical lead for the SLIMERS project, Dr Jenna Ross OBE (UK Agri-Tech Centre), said: “This exciting piece of work brought together a fantastic multidisciplinary team to develop a game-changing solution for improved monitoring of pestiferous slugs.

“By identifying these unique wavelengths of light, we can start to use these data to develop real world applications for improved slug monitoring and subsequent control.”

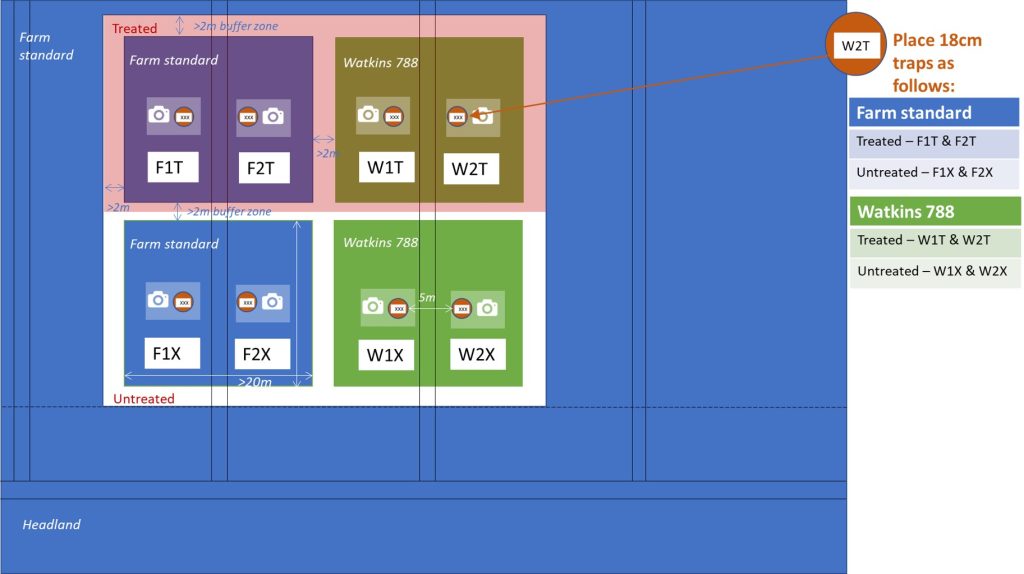

SLIMERS – Strategies Leading to Improved Management and Enhanced Resilience against Slugs – is a three-year £2.6M research programme involving more than 100 farms and seven partners.

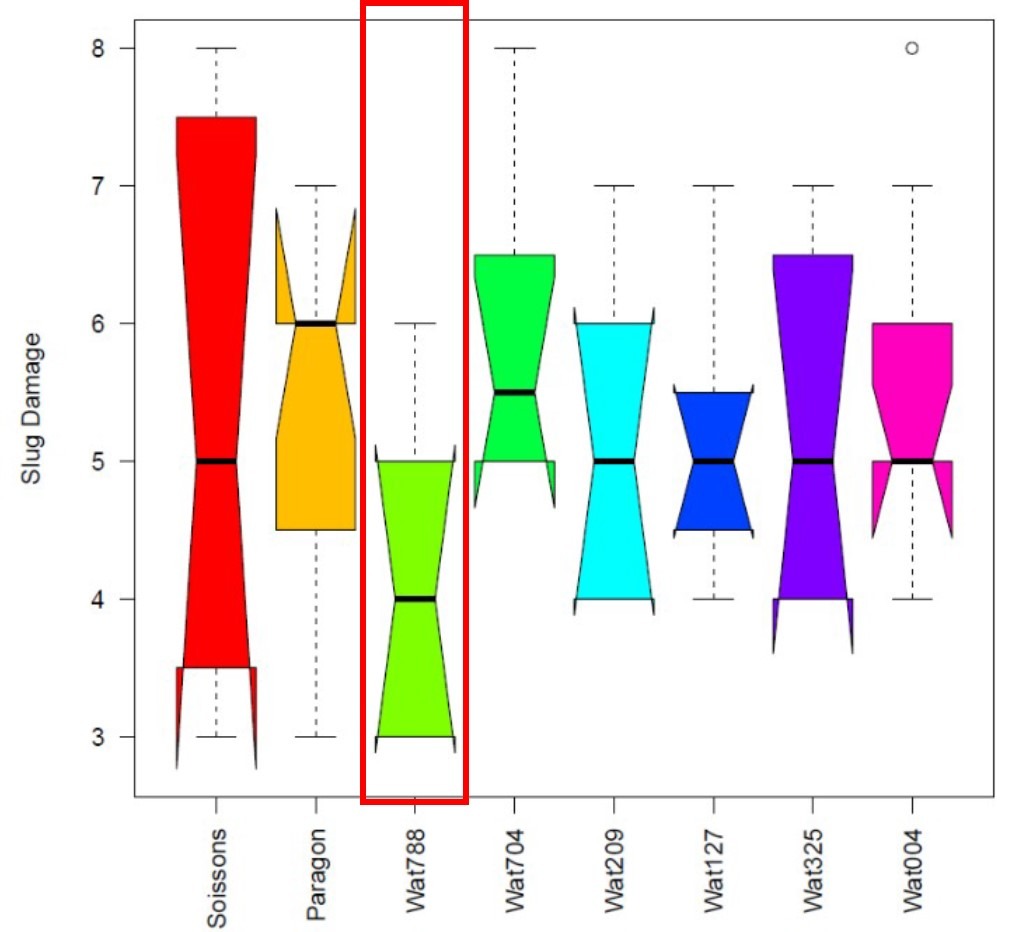

Funded by Defra’s Farming Innovation Programme, delivered by Innovate UK, the project is led by the British On-Farm Innovation Network (BOFIN). It combines expertise from partner organisations the UK Agri-Tech Centre, Harper Adams University, the John Innes Centre, Fotenix, Farmscan Ag and Agrivation. Together theconsortium is developing cost-effective forecasting and precision treatment tools, an Al-based autonomous system for the targeted application of biological control, and exploring ‘slug resistant’ wheat varieties.